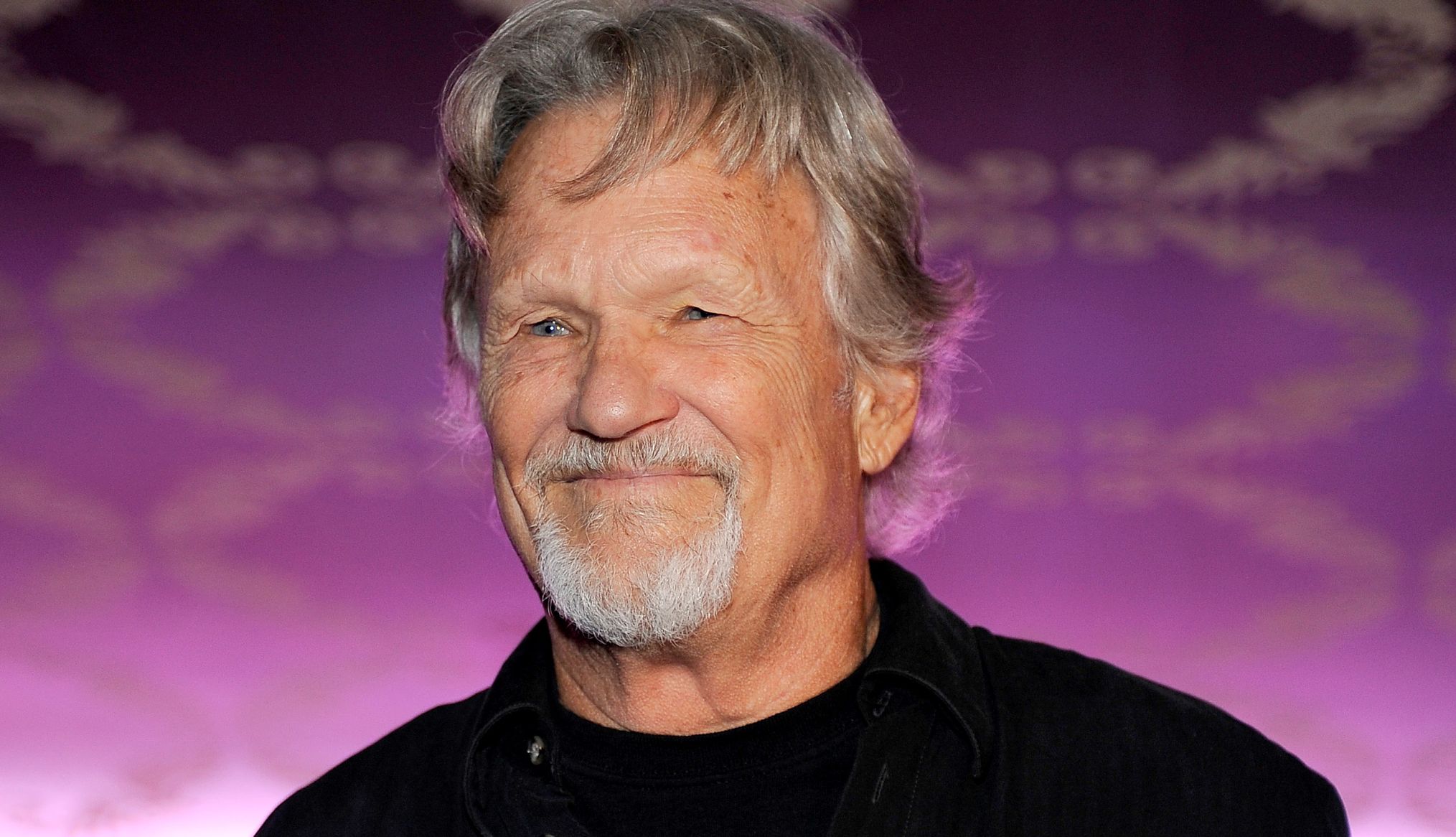

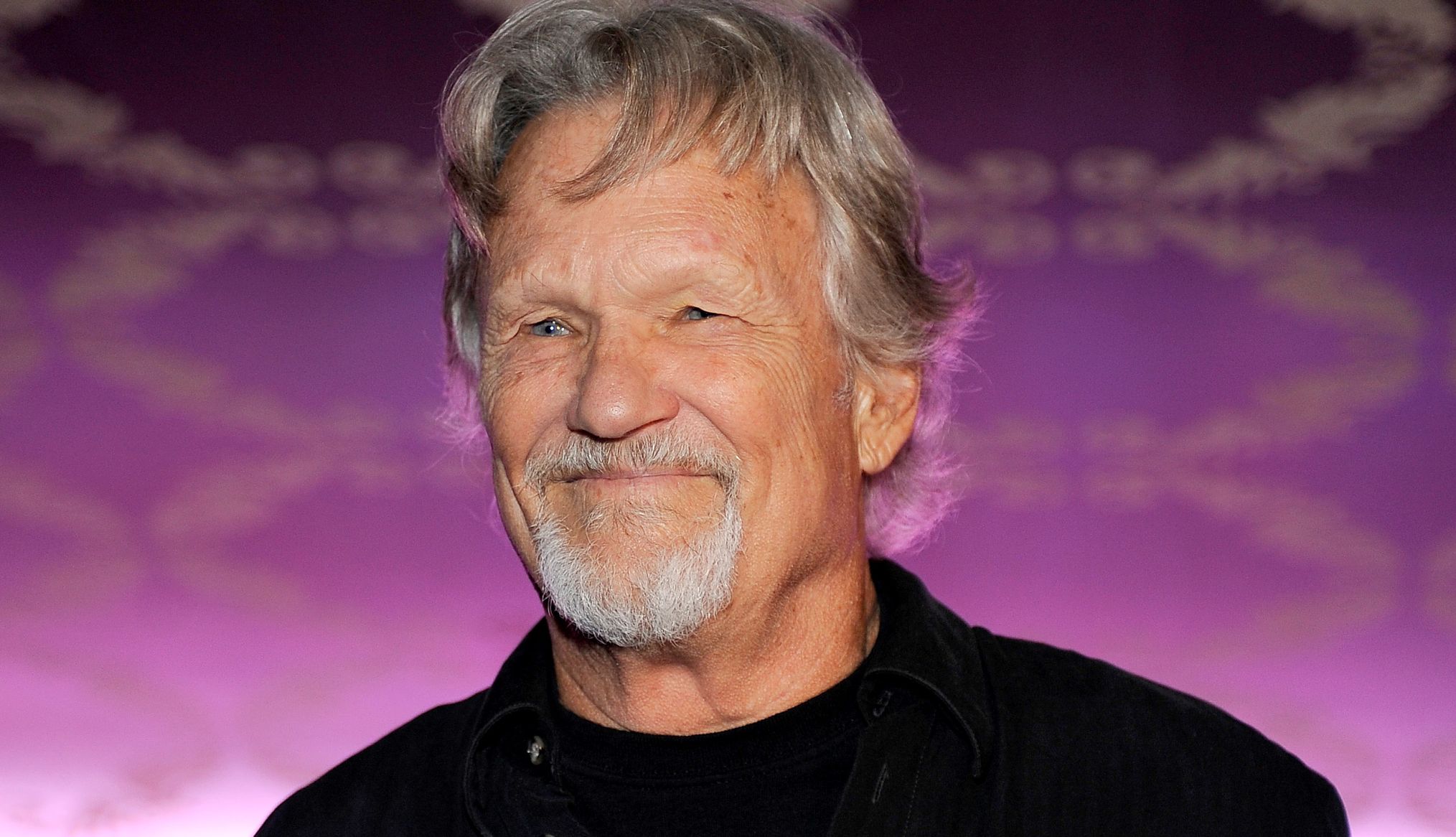

Kris Kristofferson, a Rhodes scholar with a deft writing style and rough charisma who became a country music superstar and A-list Hollywood actor, has died.

Kristofferson died peacefully at his home on Maui, Hawaii, surrounded by his family on Saturday, Sept. 28, family spokeswoman Ebie McFarland said in an email. He was 88.

Starting in the late 1960s, the Brownsville, Texas, native wrote such classic standards as “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” “Help Me Make it Through the Night,” “For the Good Times” and “Me and Bobby McGee.” Kristofferson was a singer himself, but many of his songs were best known as performed by others, whether Ray Price crooning “For the Good Times” or Janis Joplin belting out “Me and Bobby McGee.”

He starred opposite Ellen Burstyn in director Martin Scorsese’s 1974 film Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, starred opposite Barbra Streisand in the 1976 A Star Is Born, and acted alongside Wesley Snipes in Marvel’s Blade in 1998.

Kristofferson, who could recite William Blake from memory, wove intricate folk music lyrics about loneliness and tender romance into popular country music. With his long hair and bell-bottomed slacks and counterculture songs influenced by Bob Dylan, he represented a new breed of country songwriters along with such peers as Willie Nelson, John Prine and Tom T. Hall.

“There’s no better songwriter alive than Kris Kristofferson,” Nelson said during a November 2009 award ceremony for Kristofferson held by BMI. “Everything he writes is a standard and we’re all just going to have to live with that.”

Kristofferson retired from performing and recording in 2021, making only occasional guest appearances on stage, including a performance with Roseanne Cash at Nelson’s 90th birthday celebration at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles in 2023. The two sang a song Kristofferson wrote and Nelson — one of the great interpreters of his work — recorded the best-known version of.

Nelson and Kristofferson would join forces with Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings to create the country supergroup “The Highwaymen” starting in the mid-1980s.

Kristofferson was a Golden Gloves boxer and football player in college, received a master’s degree in English from Merton College at the University of Oxford in England, and turned down an appointment to teach at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, to pursue songwriting in Nashville. Hoping to break into the industry, he worked as a part-time janitor at Columbia Records’ Music Row studio in 1966 when Dylan recorded tracks for the seminal Blonde on Blonde double album.

At times, the legend of Kristofferson was larger than real life. Cash liked to tell a mostly exaggerated story of how Kristofferson, a former U.S. Army pilot, landed a helicopter on Cash’s lawn to give him a tape of “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” with a beer in one hand. Over the years in interviews, Kristofferson said with all respect to Cash, while he did land a helicopter at Cash’s house, the Man in Black wasn’t even home at the time, the demo tape was a song that no one ever actually cut and he certainly couldn’t fly a helicopter holding a beer.

In a 2006 interview with The Associated Press, he said he might not have had a career without Cash.

“Shaking his hand when I was still in the Army backstage at the Grand Ole Opry was the moment I’d decided I’d come back,” Kristofferson said. “It was electric. He kind of took me under his wing before he cut any of my songs. He cut my first record that was record of the year. He put me on stage the first time.”

One of his most recorded songs, “Me and Bobby McGee,” was written based on a recommendation from Monument Records founder Fred Foster. Foster had a song title in his head called “Me and Bobby McKee,” named after a female secretary in his building. Kristofferson said in an interview in the magazine, Performing Songwriter, that he was inspired to write the lyrics about a man and woman on the road together after watching the Frederico Fellini film, La Strada.

Joplin, who had a close relationship with Kristofferson, changed the lyrics to make Bobby McGee a man and cut her version just days before she died in 1970 from a drug overdose. The recording became a posthumous No. 1 hit for Joplin.

Hits that Kristofferson recorded include “Why Me,” “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do),” “Watch Closely Now,” “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” “A Song I’d Like to Sing” and “Jesus Was a Capricorn.”

In 1973, he married fellow songwriter Rita Coolidge, and together they had a successful duet career that earned them two Grammy awards. They divorced in 1980.

The formation of The Highwaymen, with Nelson, Cash and Jennings, was another pivotal point in his career as a performer.

“I think I was different from the other guys in that I came in it as a fan of all of them,” Kristofferson told The Associated Press in 2005. “I had a respect for them when I was still in the Army. When I went to Nashville they were like major heroes of mine because they were people who took the music seriously. To be not only recorded by them but to be friends with them and to work side by side was just a little unreal. It was like seeing your face on Mount Rushmore.”

The group put out just three albums between 1985 and 1995 before the singers returned to their solo careers. Jennings died in 2002 and Cash died a year later. Kristofferson said in 2005 that there was some talk about reforming the group with other artists, such as George Jones or Hank Williams Jr., but Kristofferson said it wouldn’t have been the same.

“When I look back now — I know I hear Willie say it was the best time of his life,” Kristofferson said in 2005. “For me, I wish I was more aware how short of a time it would be. It was several years, but it was still like the blink of an eye. I wish I would have cherished each moment.”

His sharp-tongued political lyrics sometimes hurt his popularity, especially in the late 1980s. His 1989 album, Third World Warrior was focused on Central America and what United States policy had wrought there, but critics and fans weren’t excited about the overtly political songs.

He said during a 1995 interview with The Associated Press he remembered a woman complaining about one of the songs that began with killing babies in the name of freedom.

“And I said, ‘Well, what made you mad — the fact that I was saying it or the fact that we’re doing it? To me, they were getting mad at me ’cause I was telling them what was going on.”

As the son of an Air Force General, he enlisted in the Army in the 1960s because it was expected of him.

“I was in ROTC in college, and it was just taken for granted in my family that I’d do my service,” he said in a 2006 AP interview. “From my background and the generation I came up in, honor and serving your country were just taken for granted. So, later, when you come to question some of the things being done in your name, it was particularly painful.”

Hollywood may have saved his music career. He still got exposure through his film and television appearances even when he couldn’t afford to tour with a full band.

Kristofferson’s first role was in Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, in 1971.

He had a fondness for Westerns, and would use his gravelly voice to play attractive, stoic leading men. He was Burstyn’s ruggedly handsome love interest in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and a tragic rock star in a rocky relationship with Streisand in A Star Is Born, a role echoed by Bradley Cooper in the 2018 remake.

He was the young title outlaw in director Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, a truck driver for the same director in 1978’s Convoy, and a corrupt sheriff in director John Sayles’ 1996, Lone Star. He also starred in one of Hollywood biggest financial flops, Heaven’s Gate, a 1980 Western that ran tens of millions of dollars over budget.

And in a rare appearance in a superhero movie, he played the mentor of Snipes’ vampire hunter in Blade.

He described in a 2006 Associated Press interview how he got his first acting gigs when he performed in Los Angeles.

“It just happened that my first professional gig was at the Troubadour in L.A. opening for Linda Rondstadt,” Kristofferson said. “Robert Hilburn (Los Angeles Times music critic) wrote a fantastic review and the concert was held over for a week,” Kristofferson said. “There were a bunch of movie people coming in there, and I started getting film offers with no experience. Of course, I had no experience performing either.”